Transformation of the Swiss energy landscape

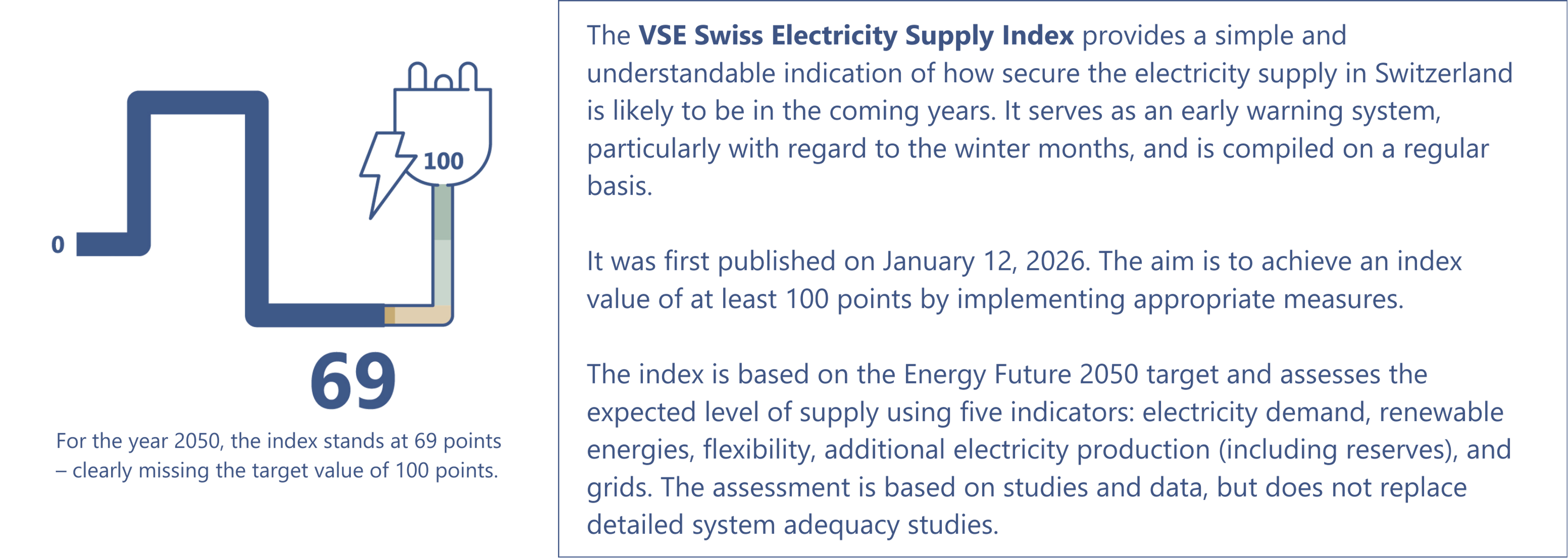

At the beginning of 2026, the VSE launched the VSE Electricity Supply Index. The aim is to assess the long-term security of electricity supply up to 2050. The index highlights where the biggest gaps between demand and reality currently exist in the Swiss electricity system. The VSE not only highlights the gaps in security of supply, but also presents solutions for bridging them. This requires ideology-free thinking in scenarios. With the Electricity Act, which came into force on January 1, 2025, the Swiss electorate set concrete goals for the transformation of the Swiss energy system. These goals are intended to ensure Switzerland's security of supply.

IFBC spoke with Martin Schwab, President of the VSE, CEO of CKW, and member of the Axpo Group Executive Board, to gain an in-depth insight into the key challenges and opportunities facing the Swiss energy industry.

Put simply, Switzerland's electricity supply requires sufficient domestic production, an efficient grid, and adequate integration into the European electricity system. The trilemma of electricity supply consists of three dimensions: security of supply, sustainability, and economic efficiency. It is a trilemma because not all three dimensions can be fully optimized at the same time.

Ensuring long-term security of supply is stalling in several areas: the expansion of renewable energies is not progressing quickly enough. Some of the 16 hydropower projects agreed upon at the round table are being called into question. Wind energy is meeting with fierce resistance in many locations. Despite subsidies, alpine solar projects are often uneconomical. Only the expansion of solar energy on infrastructure is progressing, but this is leading to ever-increasing surpluses in summer and low security of supply in winter. The heavy subsidization of summer electricity production by solar power plants also leads to economic disincentives and overproduction. The necessary grid expansion is also stalling due to costly approval processes and local opposition. And finally, optimal integration into the European electricity system requires an agreement with the European Union (EU).

A major challenge is to communicate these complex interrelationships in a simple way and thus pave the way for the transformation of the Swiss energy system. If we fail to reach a consensus across all stakeholder groups and develop a joint plan, we will most likely find ourselves in a situation again in a few years' time where we need power plant capacity at very short notice. In 2022, we built a gas-fired power plant in Birr under emergency legislation; it is essential that we avoid another such situation.

The VSE electricity supply index conveys the existing gap in a very understandable way. It is an attempt to simplify the complexity of the Swiss electricity system. Total electricity consumption in Switzerland is around 60 terawatt hours, and with the phase-out of nuclear energy and the – hopefully – decarbonization of heating and private transport, there will be a shortfall of around 50 terawatt hours.

Since supply is particularly critical in winter, more winter production from renewable energies and expansion of the grid are needed, as well as an agreement with the EU on the best possible integration of Switzerland into the European electricity grid. The VSE Electricity Supply Index Switzerland 2026 also shows the urgency: it stands at 82 points in 2035 and 69 points in 2050. The impending supply gap in 2050 could be closed by reducing electricity consumption at peak times, increasing renewable energies, extending the operating life of existing nuclear power plants, increasing flexibility such as storage, additional electricity production, e.g., from gas-fired power plants, and expanding the grids.

Without an agreement with the EU, electricity imports and exports across borders will also be affected. In the future, we will be able to quantify the effects of measures – even if this involves many assumptions: We estimate that the electricity agreement will improve the electricity index by 14 points, as integration into Europe will be significantly improved. On the other hand, we lose a few points if the two wind initiatives (minimum distances for wind turbines and mandatory municipal referendums) are accepted, which would probably prevent the construction of a large proportion of wind power projects.

Reduced to a number of points, the effects of individual socio-political decisions can be discussed objectively. The aim of the new index is also to compare the measures for security of supply with each other. For example, we would need a three-digit number of wind power plants to compensate for the rejection of the electricity agreement with the EU. This allows us to provide transparent and fact-based information. And Switzerland, for its part, can decide how it wants to achieve the 100 points. The index clearly shows that Switzerland faces major challenges in ensuring future security of supply within the time available while at the same time guaranteeing globally competitive energy prices.

This transformation is a race against time. Switzerland's security of supply will remain critical if we do not take decisive action. Parliament has not been idle – objections to the 16 hydroelectric power plants can no longer be brought before the Federal Supreme Court. The construction of 16 hydroelectric power plants would help us get closer to our goals. The plan was to be able to produce around 2 terawatt hours, but due to obstacles, resistance, and a lack of economic viability, it will probably be closer to 1 terawatt hour.

One terawatt hour is not nothing, but it does not solve the problem. For example, stricter residual water regulations will likely result in the loss of more than 1 terawatt hour over the next few decades. If we phase out nuclear energy, Switzerland will be short nearly 50 terawatt hours of electricity production annually until 2050 if electricity consumption rises to approximately 90 terawatt hours due to the decarbonization of heating and transportation. In addition, we are also in a neck-and-neck race in global politics: data centers, artificial intelligence, and new technologies are becoming a strategic locational advantage, and Switzerland must decide whether it wants to participate in this; but to do so, we also need globally competitive electricity prices.

I am a big fan of the political system in Switzerland, namely direct democracy and subsidiarity, i.e. that ultimately the municipality decides what is built on its territory. Unfortunately, our political system is hardly compatible with the acceleration of infrastructure construction. We also need a socio-political consensus that we must build the necessary infrastructure to achieve our climate and energy policy goals.

The task of the VSE is to show what works and what does not. To put it bluntly, the question for winter electricity production is: where do we build the necessary hydroelectric power plants and wind turbines, how long do we use nuclear energy, and how many gas-fired power plants do we operate? Realistically, we will build some hydroelectric and wind power plants and, due to time constraints, cover the rest with gas-fired power plants to ensure our security of supply. Doing nothing is not an option.

Basically, the willingness to invest is there and there is no shortage of capital. However, there are considerable uncertainties due to lengthy processes, environmental assessments, and participation procedures. You have to have a lot of patience and a high risk tolerance to invest substantially in renewable energies at all. Take the "Lindenberg Wind Farm" project in the canton of Aargau as an example. The turbines could have made a significant contribution to the electricity supply during the winter months and were praised for their environmental compatibility. After more than ten years of planning and several million dollars in project costs, the project was rejected at a municipal assembly. This shows that private investors in Switzerland are unlikely to invest significantly in renewable energies if there is a threat of politically motivated project cancellation.

One entrepreneurial approach would be for Switzerland to hold an auction for flexible winter electricity production. The tender could read: "Dear electricity industry, we need a commitment from a supplier for 1,000 megawatt hours from December to March, and Swissgrid wants to be able to call on this flexibly. At what price can you provide the 1,000 megawatt hours?" Every producer can bid, and the cheapest will be awarded the contract for 20-30 years. In such a scenario with 1,000 megawatt hours (flexible) without a production guarantee, this would mean the construction of gas-fired power plants. These are relatively inexpensive to build and can be ramped up and down very flexibly – even several times a day. We are therefore spending money so that we can access winter electricity flexibly and have sufficient winter production reserves. The gas tenders currently being issued by the federal government partly follow this logic. Emergency power plants are being built that will only be used when needed. This is how we are creating a local winter reserve.

According to current legislation, we can import up to a maximum of 5 terawatt hours of electricity. This seems to me to be about the right amount. In the event of electricity shortages in Europe, it would be difficult to purchase more – an import strategy always requires someone who is able and willing to export. We have to assume that every country will prioritize its own supply, and if it gets very cold in Europe, the ability to import may be lost or reduced. Switzerland could probably save the 5 terawatt hours – with effort and economic consequences.

Integrating Switzerland into the European electricity market – for example, through an electricity agreement – increases security of supply in Switzerland. Better integration of Switzerland into the European market also means lower prices for Swiss consumers. Grid stability also increases, as Swissgrid can respond better and faster to grid fluctuations through optimal integration into the European market.

The "Netzexpress" will allow grid projects to be planned, approved, and implemented more quickly. The economy and the population need more electricity due to the decarbonization of heating and transport, but also due to the potentially increasing number of data centers (e.g., for AI). Added to this are influences such as climate change and geopolitical upheavals, which we must deal with. If we do not succeed in drafting and implementing a joint energy plan , it will be difficult to guarantee security of supply. That is why we need more objective socio-political dialogue and consensus without dogmatism in order to strengthen acceptance of the electricity infrastructure among the economy and the population.

Martin Schwab has been President of the VSE since June 2024, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of CKW AG since April 2018, and a member of the Executive Board of Axpo Holding AG since February 2011. He holds a degree in business administration HF, is an expert in accounting and controlling, and has an MBA from the University of Rochester, N.Y.